April 8 quote by Naomi Klein does it for me. .. bit by bit, hour by hour, day by day,…

CO2-equivalent Update

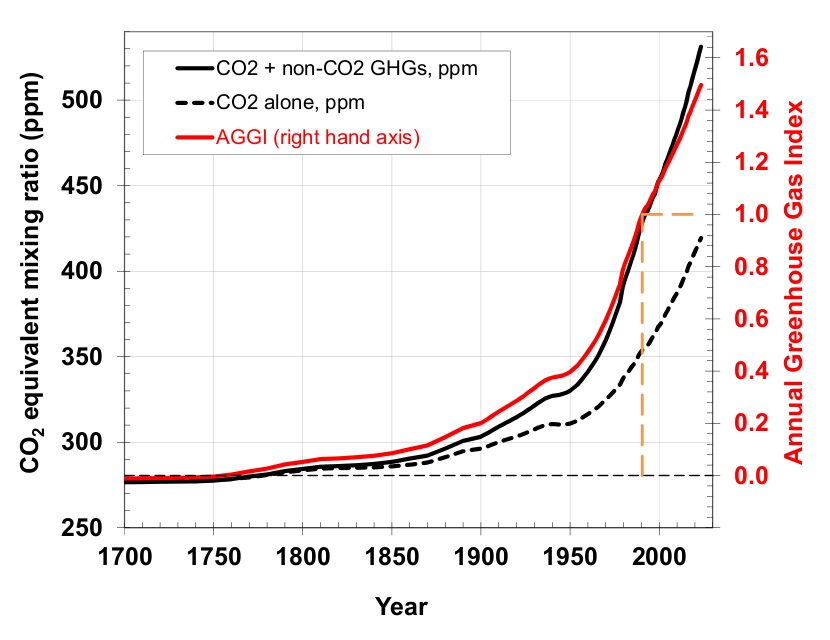

Well, it finally happened. NOAA published an update to the AGGI (Annual Greenhouse Gas Index), including their best estimate of CO2e, as of 2023. And without postponing the reveal one moment longer, their value was CO2e = 534 ppm. And, drum roll, the value I posted in my article on CO2e was 532 ppm.

I’m going to count this as a win. I would be much happier if my number exactly agreed with NOAAs. Even after multiple emails and attempts to contact NOAA, I continue to be frustrated by their lack of response. Hey, NOAA, are you there? It’s me. Eliot.

I’m going to digress for a moment and say a bit about why CO2e is important to understanding the future we’re headed towards, and offer a caution about its computation.

The key number in considering the rate at which the planet is heating is called the “equilibrium climate sensitivity” or ECS. The ECS is the amount that the Earth’s surface temperature will increase after a doubling of CO2 in the atmosphere and letting all of the associated Earty-system feedbacks play out and stabilize. But CO2 is not the only GHG, so that doubling can also take place by proxy through atmopsheric methane, N20 and other GHGs.

CO2e and ECS work together. We are only interested in CO2e because of its implications towards future planetary heating, knowing the ECS. But understanding how the ECS is computed also gives us guidance for the correct way to compute CO2e.

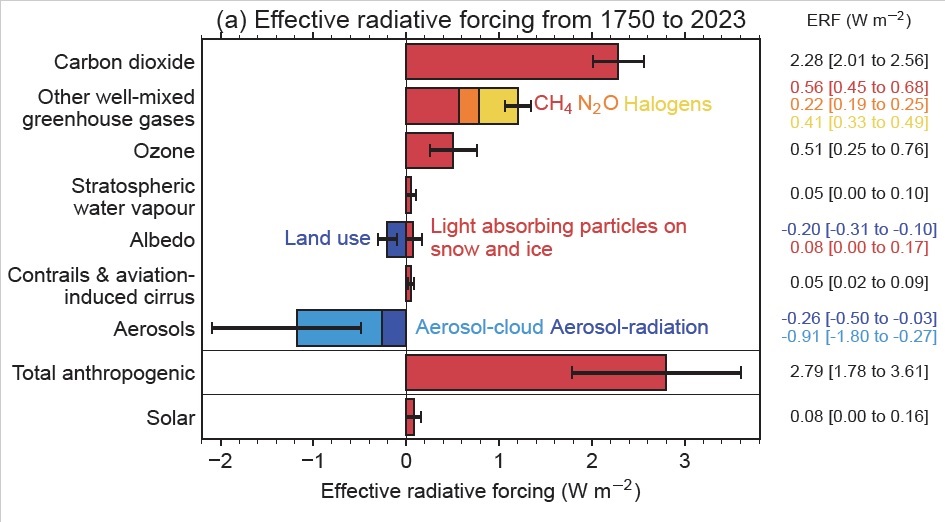

This guidance is especially important when discussing water vapor and ozone. Don’t they warm the planet too? Shouldn’t they be included in my computation of CO2e? This image from Copernicus certainly makes it look that way. We can see the direct impact of water vapor and ozone on heating the planet, and isn’t heating what CO2e is all about?

The reason that water vapor and ozone aren’t counted is very important when talking about CO2e. In short, they are secondary effects.

Water vapor and ozone are part of the multitude of feedbacks occuring in the Earth-system in response to increasing GHGs. Yes, ozone and water vapor directly warm the planet, they have a positive forcing impact. But, like all the other feedbacks that are happening right now and forecast to happen in the future, secondary feedbacks should not be counted towards CO2e.

The most commonly quoted value for the ECS is 3°C, though there is a lot of debate about this (the accepted range is from about 2°C to about 5°C). When computing the ECS, the modeling that takes place assumes that the heating of the planet will cause the release of these secondary gasses and other feedbacks that accelerate warming. In other words, water vapor and ozone are already accounted for in the value of the ECS.

The ECS takes into account all of the real world feedbacks that increasing GHGs cause. As Michael Mann explains it:

“It’s critical to recognize the key role played here by feedback mechanisms. In the absence of amplifying feedbacks, that is, if the only factor was the increase in the atmospheric greenhouse effect, the value of ECS would be around 1°C (2°F). We would only get 2°F of warming for a CO2 doubling. Unfortunately, the reality is that key amplifying feedbacks kick in once we warm the planet.”

This is the key point to understand: even though water vapor & ozone are both greenhouse gasses, even though they both warm the planet, we would be double-counting them if we included them in our computation of CO2e. Be especially cautious when people bring up water vapor or ozone as something unaccounted for in the forecasts of global heating. Yes, water vapor and ozone are accounted for. They are in the value of the ECS.

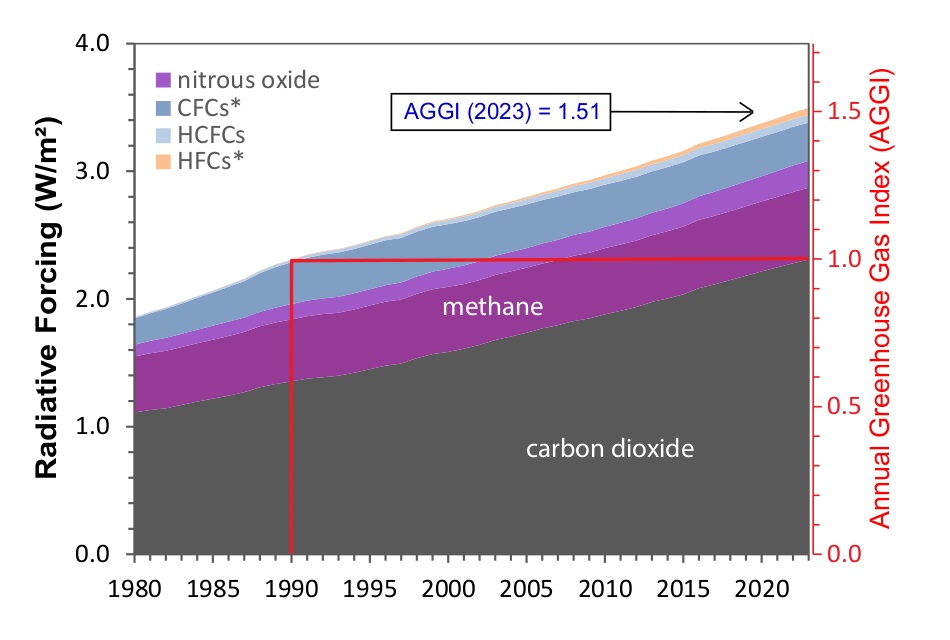

Okay, back to the main topic. Here is the key image from the NOAA paper, showing CO2e = 534 ppm:

The reception to my nerdy article on CO2e showed more engagement than I expected. A surprising number of readers followed my tangled web of explanations and expressed their gratitude. There were quite a few insightful questions and comments. A few challened me outright. And yes, I got the questions. What about water vapor? What about ozone? That’s why I pre-emptively addressed these questions in this article.

And then there were just the folks telling me I was wrong. We’re really at CO2e = 560ppm. So-and-so said we’re really at CO2e = 800 ppm. How about 2,000 ppm? Why not 10,000 ppm? And so on.

I personally believe the first way I did the computation was the correct way, using “Global Warming Potentials” and molar-eqivalents. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get all the information I needed to make that method work. I didn’t have information about GHGs other than CO2, CH4 and N20. And there are a lot more GHGs that must be considered in a computation of CO2e than just those three. As the following image from the NOAA paper shows, I would need to know every halogenated GHG and the associated GWP:

And so, the first method I used led to a value for CO2e that was way too low. It was a fail.

My second try to get a value of CO2e for 2023 was using a substantially more indirect method, using data available for “effective radiative forcing” and the Stefan-Boltzmann law.

It’s frustrating to go this indirect route, but lack of data and lack of response from NOAA made it my only recourse. And the number I came up with was close enough to not make much of a difference to anyone other than a data nerd who wants to get it right. And this is the method that led to my 2023 value of CO2e.

So, I’m satisfied for now with how this has all panned out. The information and discussions I’ve had about this question have taught me a lot about the data and various computational methods. But, I’ve also learned a lot about misinformation and just how frustrating it can be to deal with it head on. I’m not sure it’s my thing to have those battles, but getting the right answer has always been my goal.

This is confusing to me. Pre-industrial the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere was about 280ppm. But there was significant amount of nitrous oxide and methane in the atmosphere pre-industrial. Why is the CO2 equivalent mixing ratio 280ppm? Surely with the nitrous oxide and methane in the atmosphere, the CO2 equivalent must have been significantly higher than 280ppm pre-industrial? What don’t I understand?

My first article addresses this question. See “the third mistake” and it’s fix.

Fair question. Here are all the greenhouse gases with historical concentrations and projected out until 2500. https://gmd.copernicus.org/articles/13/3571/2020/

Thanks! Shame on NOAA for not making that clear.